One of the key and central buildings of the mediaeval and early modern town was the parish kirk. By the eighteenth century many churches were in poor condition, as well as being too small for a growing urban population. Where there was a large building available, such as a cathedral or former monastic church, part of this was often restored for use as a parish church, as at Paisley (1788), Dunkeld (1815) and Culross (1824). In most parishes, however, the church was completely rebuilt during the long eighteenth century, usually on the old site, though sometimes on a new one, as at Tain. Rebuilding activity peaked in the first decade of the nineteenth century.

New churches of the mid to late eighteenth century could often be plain, and sometimes awkward. By the early nineteenth century they were generally more confident and stylish. Examples include Wigtown (1730), Selkirk (1747), Hawick (1763), Saltcoats (1774), Coupar Angus (1780), Kirriemuir (1786), Duns (1790), Rutherglen (1794), Beith (1807), Melrose (1808), Clackmannan (1814), and Whithorn (1822).

A large number of these new churches, however, were themselves replaced within the next century as urban populations continued to increase, and building fashions changed.

Annan Old Parish Church, built 1780-90,

with the spire added 1798-1801.

© SCRAN/Dumfries and Galloway

Council

|

St Michael's Church, Dumfries,

1742-9. |

St Nicholas' Church, Lanark, 1774. |

St Columba's Church, Stornoway,

1794. |

St Clement's Church, Dingwall,

1799-1803. |

The eighteenth century saw the beginning of splits in the established church, and the building of new churches, chapels and meeting houses. The first secession was in 1733, but in 1744 this group split again into ‘Burghers’ and 'Antiburghers’, and later each group split in two, ‘Old Light’ and ‘New Light’, both ‘New Light' groups merging in 1820 to form the United Secession Church. In 1761 another secession formed the Relief Church. To these were added nation-wide movements such as Methodism.

St John's, Inverkeithing, built as a Burgher

chapel in 1752, altered 1798-9.

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

The number and range of ‘dissenting

congregations’ was a statistic noted

by John Wood in the commentary attached to his town plans of the 1820s.

The figure does seem to bear some relationship to how industrialised

a town was, and the number of incomers attracted to it. Dundee, for

example, had the Glassite sect, founded in the area in the 1720s, an

Associate congregation from 1738, Methodists and Congregationalist from

the 1760s, Unitarian, Relief and Baptist congregations from the 1780s,

as well as a Roman Catholic mission. And for most of the period Dundee

had both an ‘English’ and a ‘Scottish’ Episcopal

congregation.

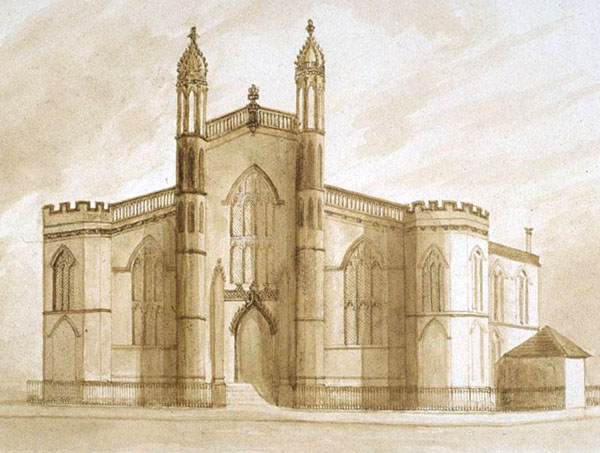

St Mary's Episcopal Church, Glasgow, designed

by Robert Scott in the 1820s, now demolished.

© SCRAN/Glasgow

University Library

The Episcopal church had been split in the

early eighteenth century, between ‘Scottish’ congregations

whose ministers did not recognise the Hanoverian government, and ‘English’

ones which did. By the early nineteenth century ‘English’

congregations were growing. Many Scots who had served in the army, or

gentry educated in England, belonged to the ‘English chapel’,

and the social cachet attracted others. The two groups merged in 1829.

The second decade of the nineteenth century saw the building of many English

chapels, and their presence in a small town can be seen as an indicator

of its being a leisure town.

There was no English chapel in Glasgow, but by the 1820s they were present

in places such as Banff, Brechin, Cupar, Elgin and Kelso.