To

return to the previous page click the blue arrow at the top right

of this page

or the one at the bottom right.

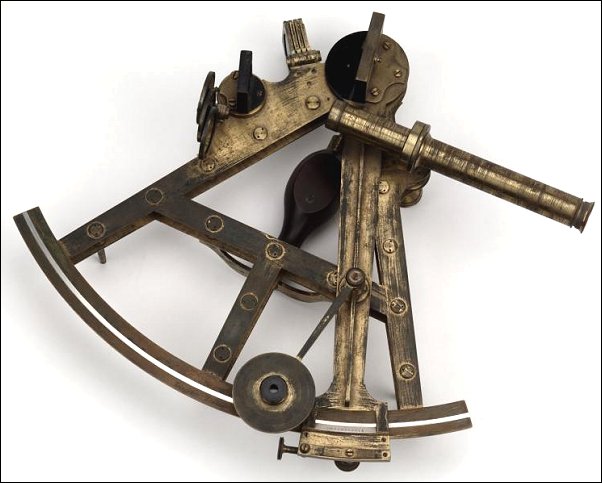

This

sextant was used to measure the angle of a heavenly body, such as

the sun or a star, above the horizon. The maximum height (zenith)

of heavenly bodies changes depending on how far from the equator

the observation point is. Therefore, fishermen and whalers could

use this measurement to calculate their latitude.

The

sextant is very finely made of brass, with glass fittings. There

are two mirrors: the index mirror is fixed to a sliding arm (the

index). The horizon mirror is half mirrored and half window. There

are also shade glasses for use when looking at bright objects, a

120 degree scale, a magnifier and a telescope.

The

angle was measured by lining up the telescope so that the horizon

could be seen through the window part of the horizon mirror. The

index was moved until the reflected light of the sun or star was

seen in the mirrored half. The height could then be read from the

scale, using the attached magnifier.

The

design for this type of sextant was patented in 1788 by Edward Troughton,

a scientific instrument maker based in London. This brass example

was made around 1820, probably by Troughton.

The

10-inch ‘pillar frame’ sextant has two thin frames of

plate brass held together by a series of brass pillars. It has a

platinum scale (which would not tarnish), an early example of the

recently discovered metal being used in instrument design. The English

chemist, William Hyde Wollaston (1766-1828) managed to isolate platinum

chemically in 1804. Troughton, who had introduced a new method of

engraving sextant scales in 1785, realised that the hardness of

this metal made it ideal for scale engraving.

©SCRAN/National

Museums of Scotland

Sextant, 1820

|