The long eighteenth century saw a rise in the proportion of the population living in towns from about 10% to nearly 30%. By the 1820s the towns they lived in had been substantially rebuilt, with new public buildings, and new suburban developments. Houses were larger, better built, and their furnishings more numerous and more comfortable.

The middle class was getting larger, with increasing numbers joining the professions. The new academies were offering a broader and more scientific education, and also evening classes for adults. But class distinctions were increasing, reinforced geographically by the building of new houses and streets, mainly for the middle classes.

By the 1820s trades and merchant guilds were becoming increasingly irrelevant

to commerce and industry, and had no place in the new industrial towns

which were growing up. As factories

grew in size, they moved to larger towns which could provide a guaranteed

workforce, leading to the decline of some smaller towns.

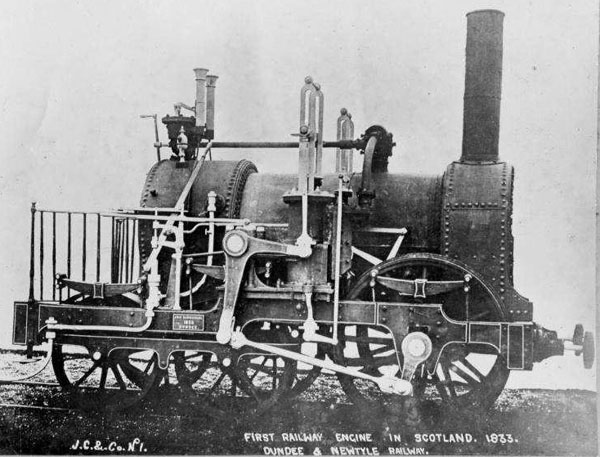

The first railway engine

in Scotland, on the Dundee and Newtyle Railway, 1833.

©

SCRAN/National Museums of Scotland

As transport became faster and more comfortable,

fewer travel towns were needed. The process started in the eighteenth

century with turnpike roads, and bridges, then by the 1820s there were

steam boats. But the greatest change came in the mid nineteenth century,

with the building of railways, which further speeded up travel, but sometimes

also changed travel routes, leaving some former travel towns by-passed

and redundant.

Among the Scottish towns which flourished

in the eighteenth century, there were winners and losers in the nineteenth.

Some, such as Kilmarnock and Kirkcaldy, developed industrially, and grew

fast, in the process rebuilding their town centres yet again, thereby

obliterating much of their eighteenth century townscape.

Others fared less well. As well as lack

of industry, and changes in travel patterns, some towns were overtaken

by more ambitious neighbours. Cupar, for example, had been a leisure town,

attracting people wanting a comfortable retirement. But by the 1840s its

neighbour St Andrews was being deliberately developed to appeal to the

same market, and with its university, its beaches and its golf links it

soon had more to offer. Other towns, however, such as Elgin, Kirkcudbright

and Nairn, continued to attract genteel retirees throughout the first

half of the nineteenth century.

Wooden model or toy bathing machine.

© SCRAN/Museum of Childhood,

Edinburgh City Museums

Some towns found their character changed

by the march of progress. Peterhead and Fraserburgh, which at the beginning

of the nineteenth century had offered mineral wells and sea bathing, soon

became busy fishing ports and lost their attraction to summer visitors.

Meanwhile new seaside resorts were being established, such as Portobello.

But it is in the towns which were left behind by the march of progress that the best architectural evidence survives of their Georgian heyday.

| Next | ||