Urban buildings were not created in isolation, but reflected the community within which they were constructed. Organisations and individuals who could afford new buildings did so not simply for their own satisfaction and comfort, but as a statement in the townscape, an expression of self-confidence, whether personal or civic. By the later eighteenth century buildings, and indeed whole streets and areas, were statements of fashion, style and modernity in a fast-changing world.

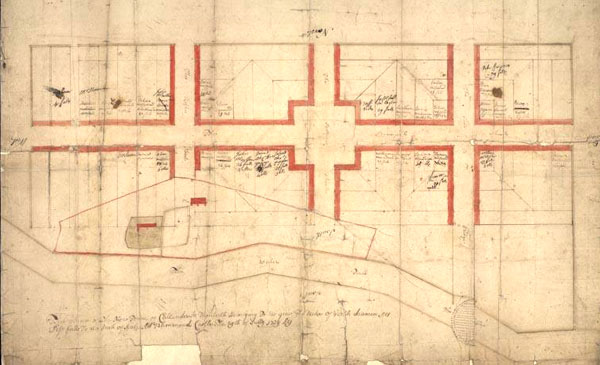

Feuing plan of the new town

of Callender in Menteith, the property of the Duke of Perth, drawn in

1739.

© SCRAN/National

Archives of Scotland

Mediaeval burghs had been laid out with

simple but generous plans, and most did not fill up all their vacant

plots until well into the eighteenth century. When they did, and there

grew up a demand for housing outside the town centre, grid-plan suburbs

tended to be developed. Normally a landowner would decide that he could

get more money from feuing land for housing than he could by continuing

to let it out for agricultural purposes.* Streets were laid out, and

plots defined along them. These plots were then sold, usually by auction,

and with restrictions on the type of building, minimum sizes and materials,

and the line of the street frontage. Sometimes a developer built whole

streets to a standard design. In other cases, a mason might buy a few

plots, build a group of houses, keep one to live in and sell the rest.

* Feuing is a Scottish form of

leasehold whereby the purchaser pays a lump sum of a fixed number of

years' rent, then continues to pay an annual rent, but the tenancy is

for life, and can be sold or inherited. As the rent or 'feu duty' was

fixed, the effect of inflation was to make feuing in the long term little

different from freehold purchase.

Town plan of Irvine, 1819, surveyed by

John Wood (c.1780-1847). The old town stands on the east side of the

river, with the academy in 'an airy situation' at the north end. To

the west is the newer burgh of barony of Fullarton, connected to Irvine

by 'a handsome stone four-arched bridge' built in 1746.

©

SCRAN/National Library of Scotland

The more ambitious or self-conscious town

councils took some initiative in founding or encouraging such ‘new

towns'. A new wide, clean, symmetrical street, for example, might serve

as a more impressive entrance to a town than an irregular older one. New

town developments included Keith (c.1750), Langholm (1778), Kilmarnock

(1820) and Cullen (1821). Occasionally, as at Cullen, the new town replaced

rather than extended the older burgh.

Some new towns were quite simple, and some contained a mix of industrial and residential development. But they all served to change the way the burgh worked. Those living and working outside the old boundary did not pay taxes, and new markets grew up outwith the control of the old closed shops of guildry and trades, which were becoming increasingly irrelevant.

The new town of Inveraray was founded in

1743. This block, called Arkland, was designed by Robert Mylne, and constructed

in 1774-5.

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

As suburbs grew, and industries moved

out, town centres could be given a facelift. As well as rebuilding town

house and church, many burghs took the opportunity to demolish derelict

buildings, remove forestairs, widen streets, and then keep them cleaner

and better lit.

At the core of these developments were two

professions, the architect and the surveyor. Architects had existed for

a while, but during the eighteenth century numbers in the profession grew,

and a clearer distinction evolved between architect and builder. What

little accurate survey work had been needed had until the eighteenth century

had been done by estate factors or schoolmasters. During the century the

profession of surveyor grew up, to lay out new roads and new towns, adding

to an expanding professional middle class.

| Next | ||