| The origins of European whaling |

|

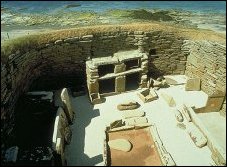

Whales and seals have been exploited in Europe for many hundreds of years. From early on, stranded whales provided not only meat but oil and bone as well. Excavation of the middens of the Neolithic village of Skara Brae on Orkney Mainland has, for example, revealed bowls carved from whale vertebrae. In Viking times walrus tusks were traded around Europe. The 12th century ivory chess pieces discovered on Lewis are a fabulous example of Scandinavian artistry. Organized whaling probably started in the Middle Ages in the Bay of Biscay where a shore-based industry exploited migrating right whales. The level of persecution was such that the local stocks dwindled and the Basque whalers had to look further afield and by the 16th and 17th centuries they were whaling along the coast of Newfoundland. However, because of the vast distances involved this early Arctic industry was doomed to failure. It was the Dutch, sailing out of Rotterdam, who were the first to successfully exploit whale stocks at long distances from home. From the mid 1600s onwards they sailed each spring to the Greenland Sea and Spitzbergen to arrive just as the pack ice was beginning to break up. There they hunted the bowhead whale, which swam in such abundance in the cold arctic waters that the supply must have seemed endless. The Dutch fleet was massive, reaching a peak of 1494 sailings in 1744. The whalers were not particularly efficient however, and each boat typically took only 3-4 whales in a season. Enough to return a profit, but possibly few enough to ensure that the "fishery" was sustainable. That happy state of affairs was soon to change. By the 1750s increasing numbers of English whalers from London, Newcastle, Whitby, Liverpool, Bristol and Hull were joining the Dutch on the annual trip. In Scotland, Leith equipped its first ship in 1750, followed by Dunbar in 1752 and Aberdeen, Bo'ness, Kirkcaldy and Dundee in 1753 and Peterhead in 1788. Among the English was a young captain, William Scoresby, who by his great navigational and hunting skills was to change the industry for ever. In the autumn of 1792 he returned to his home port of Whitby with the whalebone and blubber of 18 bowhead whales in his hold. His ship the Henrietta took 80 whales, producing 729 tonnes of oil in just 5 years. He was even more successful with his next boat, the Dundee, taking 36 whales in 1798 alone and 94 whales in 5 years. Scoresby's skill was to get in among the bowheads early in the season when large numbers of whales were confined in small areas of open water. It was as simple, and as devastating, as shooting rats in a barrel. Scoresby introduced other innovative techniques, including the crow's nest, a barrel mounted at the top of the mast which protected the lookout against the worst of the Arctic weather. Scoresby's skills ensured that he made a regular annual profit of 25% but they also spelled the inevitable end of the industry. As other British captains copied and adopted his techniques the slaughter of the whales accelerated and the stocks that had provided a sustainable harvest for over 150 years began to collapse. When Scoresby started whaling there were probably 700,000 bowheads, 40 years later they were all but gone. The Dutch industry began to languish and was effectively killed off by the long naval blockade of the Netherlands during the Napoleonic wars. By the 1820s bowheads were virtually extinct in the Greenland Sea and the British whalers were forced to move to the dangerous ice-bound waters of the Davis Strait, west of Greenland. |

|