| The Peterhead whaling trade | |

|

Home

|

The kill

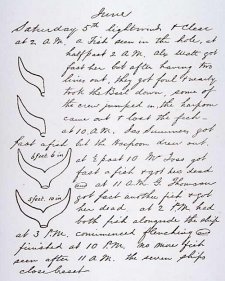

William Scoresby was clear that the success of the Arctic whalers was dependent upon the relative ease with which the placid bowhead whales could be approached. The following account of how men in rowing boats, armed with simple harpoons, were able to dispatch these huge animals is based on his own, eye-witness accounts. "Whenever a whale lies on the surface of the water, unconscious of the approach of its enemies, the hardy fisher rows directly upon it; and an instant before the boat touches it, buries his harpoon in its back. But if, while the boat is yet at a little distance, the whale should indicate his intention of diving, the harpoon is thrown from the hand, or fired from a gun, the former of which, when skillfully practiced, is efficient at 8 or 10 yards, and the latter at the distance of 30 yards. The wounded whale, in the surprise and agony of the moment, makes a convulsive effort to escape. This is the moment of danger. The boat is subjected to the most violent blows from its head, or its fins, but particularly from its ponderous tail, which sometimes sweeps the air with such tremendous fury, that both boat and men are exposed to one common destruction. The moment the wounded animal disappears, or leaves the boat, a jack or flag, elevated on a staff, is displayed; on sight of which, those on watch in the ship, give the alarm, by stamping on the deck. At the sound of this, the sleeping crew are roused, jump from their beds, rush upward on deck and crowd into the boats. The first effort of a "fast-fish", or whale that has been struck, is to dive towards the bottom of the sea. To retard, as much as possible, the flight of the whale, it is usual for the harpooner, who strikes it, to cast one or two, or more turns of the line around a bollard; which is fixed within 10 or 12 inches of the stem of the boat. Such is the friction of the line, when running around the bollard, that it frequently envelopes the harpooner in smoke; and if the wood were not repeatedly wetted, would probably set fire to the boat. The utmost care and attention are requisite, on the part of every person in the boat, when the lines are running out. When the line happens to run foul, and cannot be cleared on the instant, it sometimes draws the boat under water; on which the crew are plunged into the sea. The average stay under water, of a wounded whale is about 30 minutes. Immediately that it re-appears the assisting boats make for the place with the utmost speed , and as they reach it, each harpooner plunges his harpoon into its back. It is afterwards actively applied with lances, which are thrust into its body, aiming at its vitals. At length, when exhausted by numerous wounds and the loss of blood, it indicates the approach of its dissolution by discharging from its blowholes a mixture of blood along with the air, and finally jets of blood alone. In dying, it turns on its back or side; accompanied with three lively huzzas!" Links |

| |