‘…whenever they invade hostile territory they rigidly refuse

battle till they have fortified their camp. If the ground is uneven it

is thoroughly levelled, then the site is marked out as a rectangle. Four

gates are constructed, one in each length of wall, practicable for the

entry of baggage-animals and wide enough for armed sorties, if called

for. The camp is divided into streets, accurately marked out ….

The construction of the outer wall … is accomplished faster than

thought, thanks to the number and skill of the workers. If necessary a

ditch is dug all round ….’

So wrote Flavius Josephus, who fought first against and then for the Romans in Judaea during the late first century, and knew at first-hand how the army operated on campaign. Temporary field-works of the kind he describes are known in many parts of the empire, but more have been identified in northern Britain than anywhere else.

This camp on Trajans'

Column clearly shows the straight sides and rounded corners typical

of Roman fortifications. Inside the camp the troops' leather tents can

be seen, while at its centre the army commander (in this case the emperor

Trajan) pours a libation on an altar. A procession of priests, musicians,

and sacrificial animals heads towards one of the camp gates in preparation

for a suovetaurilia.

© Author's collection

Temporary camps, like their more permanent relations, forts, were constructed

according to an instantly recognisable formula. They were square or rectangular,

with rounded corners, and gaps in their defences were left for gates.

At least one gate was usually provided in each side, as Josephus states,

but often there were more, particularly on the longer sides of rectangular

camps. The defences were constructed by digging a ditch and throwing up

the spoil to build a rampart, which could be reinforced with a palisade

of stakes. Inside, sectors were allocated for the various units to pitch

their tents. Broad clearways ran between the tent-lines and around the

inside of the rampart to permit rapid deployment in an emergency. At the

centre of the camp stood the commander’s headquarters, where the

standards and images were displayed.

Such enclosures were usually occupied only briefly - sometimes perhaps for a single night. Because of this, and because troops on campaign carried few possessions, artefacts such as pottery or coins which might help to date a camp are rarely found. Their relatively slight defences, too, were usually obliterated by later cultivation. Fortunately their buried ditches often show up as crop-marks, and most that are known today have been discovered by aerial reconnaissance.

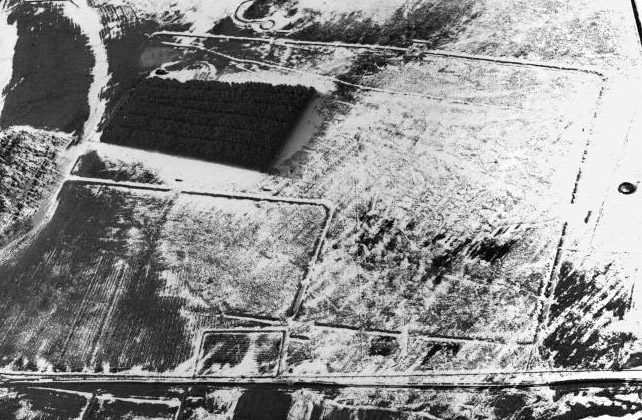

The camps at Pennymuir.

At the foot of the picture a modern minor road follows the course of Dere

Street, the Roman road. The small square enclosure by the road, and the

circular features at the top, are modern.

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

At Pennymuir, in the northern foothills of the Cheviots, the well-preserved

remains of two camps can be seen. The larger encloses 42 acres (17 ha),

and originally had six gates, of which five survive. Each gate is masked

by a traverse, or short length of ditch and rampart thrown forward of

the gap in the defences. Later a smaller camp utilised the earlier work’s

south-east corner.

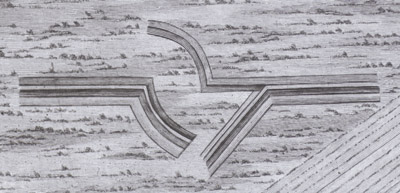

Other forms of gateway defences are known,

like this elaborate form recorded in the mid eighteenth century by General

William Roy at Dalginross in Perthshire.

© Author's collection

The camp at Dun.

© Colin

Martin

A small temporary camp at Dun (above), on the north side of the Montrose Basin, revealed by the crop-mark of its ditch. A late-first century sherd of pottery found here suggests that this camp may have been associated with Agricola’s campaigns.

The camp at Inchtuthil (centre to left)

adjacent to the fortress, a corner of which can be seen centre right.

Within the camp rows of pits appear to follow the tent lines of its

occupants.

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

Temporary camps rarely provide evidence of their internal layout, for

the tents in which the troops were accommodated leave no trace. If the

camp was occupied for some time, however, pits might be dug in front of

the tents to dispose of rubbish, or behind the rampart for latrines or

cooking. These sometimes show up as cropmarks, as here at Inchtuthil.

This camp was almost certainly built to house legionaries engaged in building

the adjacent fortress.

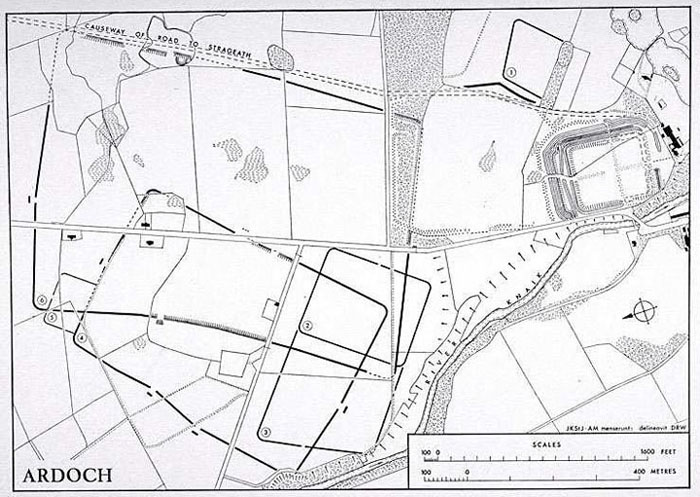

The complex of overlapping camps and

other works at Ardoch.

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

On rare occasions the relationships of camps to other features provide clues to their dates and possible associations with historically-attested campaigns. Here at Ardoch the annexe of the permanent fort intersects with the large temporary camp 7, in a manner which shows that 7 is the later work. Because it is known that the fort and (presumably) its annexe were in use until the 160s the camp is therefore likely to be later than that. Consequently its most probable association is with Severus’s campaigns of 208-210. The ditch of camp 7, moreover, intersects the defences of camp 5 at two points. Excavation at one of them has shown that camp 5 came first, but that camp 7 followed shortly afterwards. This suggests (though it does not prove) that the two camps represent successive phases of the Severan campaigns.

The camp at Burnswark in Dumfries-shire,

showing the three catapult emplacements facing the abandoned native

fort on the hilltop. In the right hand corner are the remains of an

earlier Roman fortlet.

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

Legionaries operate a catapult

from a timber-built emplacement in this scene from Trajan's Column. In

front of them slingers prepare to discharge a barrage of lighter missiles.

© Author's collection

Camps were used for many purposes - as overnight stops for armies moving through enemy territory; to provide secure enclosures for baggage animals and reserves behind a battle-line (as at Mons Graupius); or for accommodating troops engaged in building work (as at Inchtuthil). They were also used for training. Here at Burnswark in Dumfriesshire what appears to be a Roman siege has been frozen in time. Camps (this is the southern one) have been established on either side of a native fort on the hilltop. Yet there is no enemy - archaeological excavation has proved that the fort was abandoned some 500 years before the Romans arrived. In front of the south camp three mounds have been built for catapults. Stone balls flung by them have been found on the hilltop, together with lead sling bullets. What we are looking at is probably not war at all, but a major training exercise.