As far back as the fifth century BC effective medical techniques had been

developed in Greece by practitioners like Hippocrates, and in due course

their ideas were transmitted to Rome. In about 293 BC a temple was built

on an island in the Tiber to Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine, who

probably originated as a real-life doctor. Ascelpian medical practices

embraced diagnosis, drugs, and surgery, and many have a remarkably modern

ring. Preventative medicine was especially encouraged, with emphasis on

diet, hygiene, exercise, and well-regulated lifestyles.

Detail from Trajan's Column, showing

first aid being given to a wounded auxiliary soldier.

© Author's collection

By the time the Romans invaded Scotland the medical service was an important

and well-organised part of the army. To ensure good hygiene forts were

supplied with fresh water, drainage, and sewers. Bath-houses and flushing

latrines were provided.

The bath-house of the Antonine Wall fort

at Bearsden

© SCRAN/Historic Scotland

Water was obtained from wells or springs, brought to the fort if necessary by aqueducts and pipes. Clay water-pipes have been found at Newstead, while traces of aqueducts have been discovered at Fendoch and Carpow. The legionary fortress at Inchtuthil would have had to divert water from the Tay several miles upstream to ensure an adequate flow of water to the top of the plateau. This would have involved a major hydraulic engineering project which had not yet begun when the fortress was abandoned.

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

© Colin Martin

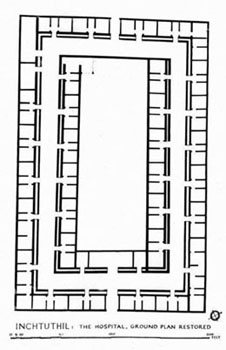

Among the timber buildings at Inchthuthil

is a vast structure measuring 300 x 192 feet (91 x 59 m). Its central

open courtyard is surrounded by double ranges of small rooms set on either

side of a corridor. This building has been identified as the legion’s

hospital, or valetudinarium. The rooms off the corridor have

been identified as wards, each large enough to have accommodated four

beds (or eight double bunks). There appear to be about sixty of them,

which suggests that one had been allocated to each of the legion’s

centuries. A long building in the

central range of the auxiliary fort at Fendoch has also been identified

as a hospital. As at Inchtuthil, its central corridor is flanked by wards.

Above: occulist's stamp, found at Tranent.

Right: fragment of amphora indicating

cough mixture.

Both © SCRAN/National Museums of Scotland

Recipies for herbal remedies and other medications can be found in Classical

literature, as well as in the archaeological record. A lead stopper from

Haltern in Germany carries the words Ex Radice Britanica (‘derived

from a type of British root’), a medicine used to cure scurvy. From

Carpow comes an amphora fragment incised with a Greek inscription indicating

that it once contained wine fortified with horehound, an aromatic herb

used in cough mixtures. A Roman occulist’s stamp has been found

at Tranent. It would have been used to seal containers of eye ointment,

and reads (reversed) L VALLATINI APALOCROCODES AD DIATHESIS -

‘Lucius Vallatinus’ mild eye-salve.’

Archaeologists have found numerous surgical instruments in Roman military hospitals. Many are remarkably similar to their modern counterparts, indicating that complex operations were routinely carried out. Service on Rome’s frontiers may have been tough and sometimes hazardous, but the troops could evidently count on a first-rate health service.