Rome’s most enduring legacy is her roads which, along with shipping

routes and rivers, provided the empire with a communications network unsurpassed

until modern times. Even today many roads still follow the courses of

their Roman predecessors. In Scotland, the Roman roads were exclusively

military, linking together forts and frontier systems.

The line of Dere Street, revealed by

later field boundaries and tracks.

© SCRAN/J Dent/Borders Council

The course of a Roman road is often revealed by the later roads, tracks,

or field boundaries which have followed it. Here the line of Dere Street,

Rome’s main route into Scotland, is clearly seen emerging from the

snow-covered northern foothills of the Cheviots, heading towards the Forth.

The road along the Gask

Ridge is visible here as a heavily cambered mound,

or agger, running through a gap in the trees. In the foreground a cross-ditch

has exposed some of the stone bottoming. Originally the road would have

been surfaced with gravel, and a steep camber was necessary to reduce

erosion by throwing off surface water.

© Colin Martin

Even where the remains of

a Roman road have been destroyed by ploughing, quarry-pits dug beside

them to provide material for their construction sometimes show as crop-marks.

Here, at Wester Drumatherty some 2 km north-west of the legionary fortress

at Inchtuthil, crop-marks identify a junction of two Roman roads. One

is apparantly heading towards the sandstone quarries on Gourdie Hill,

while the other follows a level contour into an adjacent valley, perhaps

to facilitate timber extraction.

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

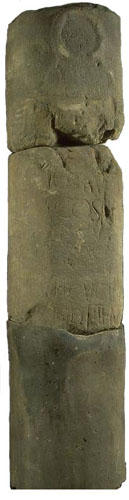

The only Roman milestone known in Scotland (right)

was found near Ingliston in the seventeenth century. It is now in the

National Museum of Scotland. Though fragmentary, its text can be restored

to incorporate the name and titles of Antoninus Pius, probably (though

not certainly) at the time of his third consulship, in 140-44. The stone

records an unknown number of miles to Trimontium

(Newstead), and was set up by the First Cohort of Cugerni. Of particular

interest is the fact that two lines have deliberately been erased. This

part of the inscription would almost certainly have included the name

of the provincial governor, and the erasure indicates his official disgrace.

It can hardly have been Lollius Urbicus, the governor of Britain under

Antoninus Pius recorded as ‘driving back the barbarians’ and

‘building another wall, of turf’ (the Antonine Wall), for

he went on to complete a distinguished and unblemished career. His successor

is not known, but a possible candidate is Cornelius Priscianus who, in

145, was disgraced for misdemeanours while governor of part of Spain.

© SCRAN/National Museums of Scotland