The two symbols of the administration of any town were its mercat cross and its tolbooth. The mercat cross, the symbol of a town’s right to hold markets, seems to have lost its symbolic importance during the eighteenth century. Between about 1750 and the 1790s many crosses were removed because they were obstructing traffic. Some were demolished completely, others relocated, often on smaller bases, in a less obtrusive position. What we see today, however, is usually a late nineteenth or early twentieth century restoration, often on yet another site.

The mercat cross at Preston, East Lothian.

© SCRAN/Edinburgh College of Art

Early tolbooths were usually towers, housing

in the basement or ground floor a cell for criminals, and above that

a weigh house, a meeting room for town council and burgh court, and

sometimes above that a drier and warmer cell for debtors. At the very

top hung the town's bell. Many towns by the early to mid eighteenth

century had added an adjacent building, usually with a large first floor

room for the use of council and court, and sometimes for public entertainments.

| Dundee, new town

house, 1732-34. © SCRAN/National Museums of Scotland |

Annan, new town

house, 1740 (steeple 1795). © SCRAN/Dumfries & Galloway Council |

Inveraray, new

town house, 1754-57. © SCRAN/RCAHMS |

Montrose, new

town house, 1762-64 (top storey added 1819). © SCRAN/RCAHMS |

Stranraer, new

town house, 1776-77. © SCRAN/RCAHMS |

Peterhead, new

town house, 1788. © SCRAN/RCAHMS |

Old Aberdeen,

new town house, 1788-89. © SCRAN/Nick Haynes |

Kelso, new town

house, 1816. © SCRAN/RCAHMS |

Almost every town in Scotland rebuilt

its tolbooth sometime between 1700 and 1825. Some produced a completely

new building, as in the case of Dundee, who commissioned the fashionable

architect William Adam to design it. Others attached new town houses

to the existing tolbooth tower. Some, such as Tain, chose to replace

the old tower with a newer one, which provided a visual focus, as well

as housing the town’s bell, and often a clock. Other towns built

smart, elegant new town houses with no tower or spire.

© SCRAN/National Museums of Scotland

© SCRAN/National Museums of Scotland

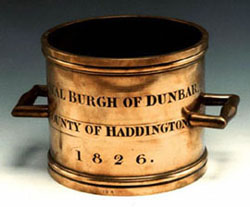

Burghs were governed by town councils,

usually self-perpetuating oligarchies,

consisting mainly of members of the merchant guild (‘guildbrethren').

A minority of councillors represented the incorporated trades. In smaller

towns, admission to these groups could be fairly flexible, and each

burgh had a slightly different ‘sett’ or constitution. The

council collected the towns’ rents, dispersed its income, and

generally kept the town running. One role was providing standard weights

and measures against which goods at markets could be checked.

© SCRAN/North Ayrshire County Museums

© SCRAN/Glasgow University Library

Most councils were reactive rather than

proactive, and much eighteenth century development was carried out by

individual entrepreneurs, whether acting in a private capacity or using

their position on the council to achieve their ends. Day to day control

was in the hands of the town officers. These were salaried posts, often

given to former soldiers, or guildbrethren who had fallen on hard times,

and might include specialists such as gaoler, bell-ringer, drummer or

piper (fife, not bagpipes). The drummer led formal processions, and made

official announcements through the town ‘by tuck of drum’,

stopping at fixed points such as the cross and the church door to read

out a proclamation or advertisement.

Town officers wore simple uniforms, and could serve as a sort of police force. There were also constables, with a range of duties, at first appointed for specific occasions, but gradually being employed on a more formal and permanent basis. It was the rapid development of towns, and the problems engendered by social dislocation and overcrowding, which led to the creation of our modern police force. After Glasgow, police forces were set up in Edinburgh in 1805, Perth in 1811, and Dundee in 1824.

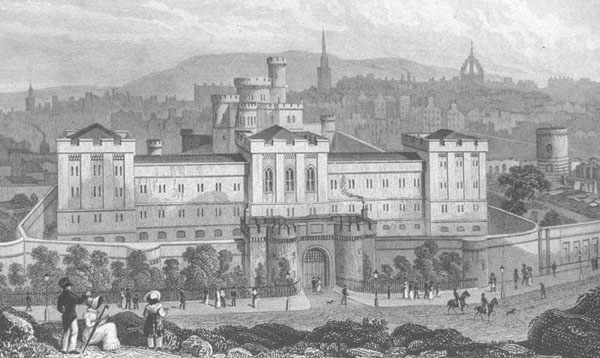

Engraving of Calton Gaol,

Edinburgh, built in 1815-17 to replace the prison in the old tolbooth.

It had 54 cells.

© SCRAN/Edinburgh City Libraries

Gradually dedicated prisons were beginning

to be built, often part of the new town house, but increasingly on separate,

out-of-town sites. These not only provided more cells than the old tolbooths,

but more humane conditions. Also established in a few large towns were

'Bridewells’, prison-workhouses to accommodate and provide employment

for the fit but vagrant poor. Edinburgh's

Bridewell was established in 1797, and it was followed by Glasgow in 1798,

Aberdeen in 1809 and Paisley in 1821. Some smaller towns wanted to establish

Bridewells, or to buy places in existing ones, but were unable to raise

the necessary money.