| The Peterhead whaling trade |

|

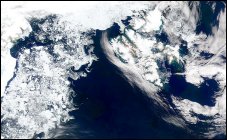

A year in the life of a whaler. With the sailing ships and rowing boats used by the Greenland fishery it was virtually impossible to catch whales out at sea. The killing took place near to the ice where the whales could be harpooned as they surfaced to breath at the edge of the ice pack, or in openings within the ice field. In 18th century, and earlier, whaling was concentrated in the Greenland Sea, between Greenland and Spitzbergen. The whaling ships sailed in March or early April, after a traditional celebratory Foy in the local taverns. On the way north the boats usually called into Orkney or Shetland to take on extra stores, and to pick up additional crew members - probably because the islanders would work for lower wages than those demanded by mainland Scots. In most years the ships reached the ice at around 79 degrees north. Once there, they sailed along the edge of the ice field in pursuit of the bowheads and the slaughter began. By July the ice was breaking up and the whales were widely dispersed and difficult to find, let alone to catch. The time had come for the ships to head home with their cargoes of blubber and bone, reaching Peterhead in July or August. By 1820, the Greenland Sea was pretty much fished out and the whalers had to seek out more profitable killing fields in the Davis Strait, to the west of Greenland. There they found an abundance of large whales and for some years large profits were made. However, the fishery was a free-for-all, with no control of catches, and inevitably this area too was overfished. As the years went by the whalers were forced to move further and further north, through the Davis Strait and up into the highly dangerous waters and ice fields of Baffin Bay. Seeking whales in these northern areas was a dangerous and difficult undertaking. The journey was now much longer and the ships had to leave Peterhead in February or early March. To the west of Greenland the whales tended to follow the edge of the ice as it retreated in the spring and advanced in the autumn. The ships stayed with the whales as long as the ice permitted and usually did not get back to port until November. To make matters worse, the ice was much heavier in these areas and when the wind was from the west the ice would close up and whole fleets of ships could be trapped for months on end. For example, in 1835 and again in 1836 large numbers of British ships were caught in the ice and were forced to over-winter without adequate supplies. Many men died of scurvy, starvation and exposure. The fate of the crew of the Dee, an Aberdeen whaler, is typical; when they reached Orkney in April 1837 only 9 of the original 46 were still alive. By the late 1820s, whales were scarce everywhere and the taking of seals became a primary objective for many captains. Seals were found in large numbers on the sea ice in the Greenland Sea and the Peterhead ships happily left the Davis Strait and returned to safer waters to the east of Greenland. Ships involved in sealing left Peterhead in February so as to reach the breeding colonies of seals at the end of March when mothers and pups were on the ice. The season was short and over within a month. Then, the masters went after the few remaining whales. Whaling was now only possible because it was being subsidized by sealing. By the 1870s the seals of the Greenland Sea were, in their turn, becoming rare and the hunt moved west, yet again, to Labrador and Newfoundland. |