Roman power was underpinned by a relatively small number of legions (about

30 in the late first century AD), placed strategically around the frontiers.

Legions were not shifted to new bases lightly, or for purely local reasons,

since such moves might upset the carefully-balanced imperial chessboard.

The decision to re-locate

a legion at Inchtuthil in Perthshire during the early 80s was therefore

one which would have been taken at the highest level.

An aerial view of Inchtuthil in its setting.

The fortress stood on the plateau surrounded by trees at centre right.

© Colin Martin

The site chosen was a plateau overlooking the River Tay, near the point at which it emerges from the Highlands to meander through the farmlands of Strathmore. The Romans recognised this as the major route between the two zones, which is followed today by the main road (the A9) and railway to Inverness. Their strategic planners grasped that this was the Highland line’s pivotal point. By placing satellite forts at the mouths of the smaller glens on either side of it all movement between Highland and Lowland Scotland could be controlled. If required, the line might also serve as a springboard for military incursions beyond

In 86, or very shortly after, the legionary chess-pieces were adjusted once more. One of the four British legions, the Second Adiutrix, was dispatched to reinforce the Danube frontier, under attack by Dacian invaders. In the down-sizing that followed forts on the Highland line and others to the south were abandoned. The legionaries at Inchtuthil, who were just putting finishing touches to their fortress-base, packed their tools and weapons and prepared to march away. Before they left they carefully demolished what they had built, and buried nearly a million iron nails rather than let them be forged into weapons by the enemy.

Photograph taken

during the excavation of the hoard of nails at Inchtuthil.

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

Unlike legionary fortresses elsewhere, Inchtuthil was never rebuilt in

stone or developed into a later town. Beneath the meadow slots cut into

the subsoil for the foundations of timber buildings survived intact, filled

with dark topsoil. Drains and pits were similarly preserved, sometimes

with artefacts sealed within them. The ditch and rampart surrounding the

50-acre fortress remained partially intact, although over time the defences

were denuded by erosion. At the four gateways, deep holes cut for the

massive wooden uprights of towers and portals preserved their details

underground. Outside the fortress the temporary camp established for its

builders remained delineated by its buried ditch, while rubbish pits within

mark the frontages of tent-lines and cooking places set behind the rampart.

Overlooking the bank of the Tay, a compound for staff in charge of the

construction programme preserved evidence of adminstrative buildings and

quarters for senior officers, including a personal bath house.

Sir Ian Richmond (right) recording legionary

ovens at Inchtuthil during the final excavation season in 1965.

© Colin

Martin

From 1952 to 1965 a campaign of carefully-focused excavation, conducted by Sir Ian Richmond and Professor J.K. St Joseph, revealed the plan of the fortress and its associated works. Topsoil was stripped away to locate the dark lines which marked the filled-in foundation trenches of timber buildings and other features. These were so regular that only small segments had to be uncovered, and the plan was built up by joining them together. Later the accuracy of this reconstruction was confirmed by air photography.

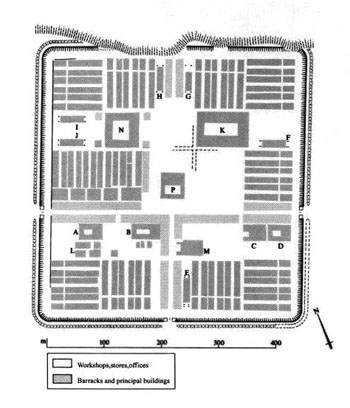

Layout

plan of the fortress. Most of the buildings around the perimeter are barracks.

Other buildings are indicated as follows: A-D tribunes' houses; E-J granaries;

K hospital; L senior doctors' quarters;

M possible workshop and stores building; N main workshop; P headquarters

building (principia).

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

Aerial photograph of the site, with features

showing up as parched lines in the grass.

© Colin Martin

The fortress was a masterpiece of regularity and ordered planning. At

its centre lay the headquarters building, where records were kept, justice

meted out, religious ceremonies observed, and the pay chests kept secure.

Here the legion’s holy emblems, including the emperor’s image

and the eagle-standard, were reverently housed and protected. Around the

inside perimeter stood rows of long barrack-buildings, each designed for

a century of about 80 heavy infantry. Quarters and administrative offices

for the centurion in charge were incorporated into each building. Six

centurial barracks were grouped in a block of three facing pairs to form

a cohort, of which nine can be traced out. A final cohort - the First

and most senior- was made up of five double centuries. The centurions

of this cohort had elaborate houses and the most luxurious of these -

that of the ‘primus pilus’, or first spear - boasted

a colonnaded courtyard and a room with underfloor heating. The First Cohort

included the legion’s veterans and specialist craftsmen. This area

also contained buildings which may have been quarters and stables for

the legion’s 120-strong cavalry troop.

A road ran around the perimeter, immediately behind the rampart, to permit the rapid deployment of troops. Other roads formed a grid within the fortress, the main ones running axially with the gates. Stores buildings lined the major thoroughfares.

Four large houses were provided for tribunes - young noblemen in imperial service whose career tracks included civilian as well as military appointments. Two others would have been on the legion’s establishment. Their quarters had not been built, although space was set aside for them. A large area had also been levelled and drained for the palatial quarters of the unit’s commander, the legionary legate, but work on it had not started. Evidently the priority had been to get the troops on the ground first.

Aerial view of two

granary blocks at Inchtuthil.

© Colin Martin

Other buildings include six

large granaries (perhaps to contain tribute from the natives as well as

supplies for the soldiers), a hanger-like workshop (it was here that the

hoard of nails was found), and a vast military hospital. Service in Caledonia

was obviously not without its health hazards.

The purposes of some of the buildings cannot now be determined, but they probably included facilities for training, small workshops, and quarters for various specialist officers.

At full strength the legion would have contained about 5,500 men.