Although antiquarians had long suspected that a Roman fort lay near the

Eildon Hills, whose distinctive triple peaks equate with Trimontium,

a place in southern Scotland recorded by the second century geographer

Ptolemy, it was not until 1846 that evidence for it was uncovered at Newstead,

on a high bluff overlooking the River Tweed. Railway builders driving

a cutting through the site discovered rubbish pits containing Roman pottery

and other remains. In 1905 James Curle, a local solicitor, began a systematic

excavation of the site which lasted for five years.

The site of Trimontium - Roman

Newstead - on a bluff overlooking the River Tweed. Parch-marks reveal

the fort just left of centre, beneath the curving line of trees. Crop-marks

in the light field (right foreground) pick out the ditches of temporary

camps and other works. Further marks can be seen in the darker fields

beyond; these include the fort's annexes which accommodated extra-mural

settlement as well as agricultural and industrial activities.

© Colin Martin

Curle’s greatest achievement was to identify several overlapping forts, representing a succession of occupations spanning nearly a century. He recognised three, and later work by Ian Richmond added a fourth. The first fort dates to the late first century, and probably represents a garrisoning of the site during the campaigns of Agricola, perhaps in 79 or 80. This was followed by a rebuilding of the fort and a massive strengthening of its defences, which can be associated with the phased withdrawal which followed the abandonment of the legionary fortress at Inchtutuil, in 86 or 87. Newstead itself was later to be abandoned, probably around 105. A third occupation dates to the Antonine reoccupation of Scotland, in 139-42. Evidence for abandonment in the late 150s followed almost immediately by a fourth rebuilding suggests that the fort was given up briefly before it finally fell out of use around 180. A small amount of material of early third century date suggests that the site was briefly visited during the emperor Severus’ campaigns, though no structural evidence for this period has been found.

The fort site from the north. Parching

reveals the enclosing playing-card-shaped rampart, and the street patterns

within. Traces of roads can be seen running from the east and south

(left and top) sides of the fort.

© Colin Martin

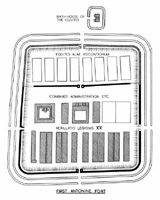

Newstead's four overlapping phases of

occupation, as revealed by excavation. From left to right they are:

(1) a fort perhaps established by Agricola c.80; (2) the reconstructed

'front-line' fort of c.90, following the abandonment of garrisons further

north; (3) the first Antonine fort, c.141/2; (4) the second Antonine

fort c.158-c.180.

all © SCRAN/RCAHMS

Curle’s work had therefore demonstrated a synchronisation between

historically attested episodes of Roman incursion into Scotland and the

successive phases evident in their forts. This synchronisation has provided

a framework for the archaeology of Roman sites in Scotland ever since.

But his excavations yielded much more. Outside the fort lay several annexes,

and within these a number of deep pits were found. Many contained only

rubbish, although this was interesting enough: broken pottery, leather

shoes, animal bones, oyster and mussel shells, and pieces of wood. However

some of the pits - especially those connected with the abandonment of

the fort in the early second century - contained the most remarkable collection

of objects yet found in Roman Scotland.

Iron face-mask helmet recovered from

a pit at Newstead. These were used by Roman cavalrymen for parade and

ceremonial purposes, not for fighting.

© SCRAN/National Museums of Scotland

The most striking discoveries were bronze and iron parade helmets belonging

to auxiliary cavalrymen. But there were also items of horse harness, domestic

implements, personal possessions, and tools for a wide range of crafts.

These objects provide a vivid picture of life in a Roman frontier post,

and many are on display in the National Museums of Scotland.

Altars dedicated during the Antonine period identify the units in the garrison at that time. There seems to have been a detachment of the Twentieth Valeria Victrix Legion, probably two cohorts strong, under the centurion Gaius Arrius Domitianus. An auxiliary cavalry regiment, the Ala Augusta Vocontiorum, was also present at the fort.

In the 1980s further excavations and geophysical surveys were carried out in the fort and its surroundings by the University of Bradford. Most of this work was conducted in the annexes, and revealed an extensive shanty-town of timber buildings set along wide streets. Some of these buildings seem to have been domestic, and perhaps housed soldiers’ families. Some have been shops, taverns, and other places of entertainment for the troops. Yet others seem to have been connected with industrial activities, or farming. Even on its remotest frontier, the Roman army seems to have been remarkably self-sufficient.

Crop-marks reveal the twin

towers defending the fort's east gate.

© Colin Martin

Over the years, fieldwork and aerial photography have continued to expand

our understanding of Roman Newstead. The fort is surrounded by ditched

enclosures. Many are temporary camps set up by armies on the move, but

others appear to be field boundaries, suggesting that the fort lay at

the hub of a small estate which contributed to its well-being. On the

frontier, it appears, Roman forts generated their own industrial and economic

activities, trading with their neighbours to secure for their garrisons

the high standards of living to which their pay entitled them. The natives

probably derived little direct benefit from this boom. More probably they

underpinned it by providing dues of grain, livestock, and slaves. Only

their leaders seem to have obtained much in the way of Roman goods, as

finds from high-status native sites imply. These were more probably inducements

for good behaviour than indicators of economically-based trade.

Site of the recently-identified Roman

amphitheatre at Newstead. It is visible near the centre of the picture

as a parched hollow. The Tweed is at the lower right.

© SCRAN/RCAHMS

Newstead was the largest and most important fort

in southern Scotland, a key point in the road system which linked the

network of garrisons. A milestone at

Ingliston, west of Edinburgh, refers to Trimontium as the system’s

hub, and it was at Newstead that Rome’s Great North Road, Dere Street,

crossed the Tweed. Traces of a stone bridge could still be seen there

in the eighteenth century. More recently the remains of an amphitheatre

have been identified outside the fort. It is the most northerly one known

in the Roman empire.